Over the past few months, in the lead-up to the publication of my book, I’ve used this space to share brief excerpts. Now the book is out! If you want a copy, you can order it from the University of Michigan website (or other popular book ordering places!). In case you haven’t decided whether this book would be a good addition to your library, here’s a brief overview.

I wrote Thriving as a Graduate Writer because I believe graduate students can reframe their experience of academic writing. We all know that writing is at the heart of the academic enterprise. It is both how we communicate and how we are assessed. That combination can be brutal for any writer, and it’s particularly fraught for graduate writers, who must learn disciplinary writing practices while being judged on their early efforts. Recognizing these challenges is valuable; graduate students are better off knowing that their difficulties with academic writing are entirely legitimate. This recognition, however, is only the first step. The next step must be to find ways to ameliorate those challenges.

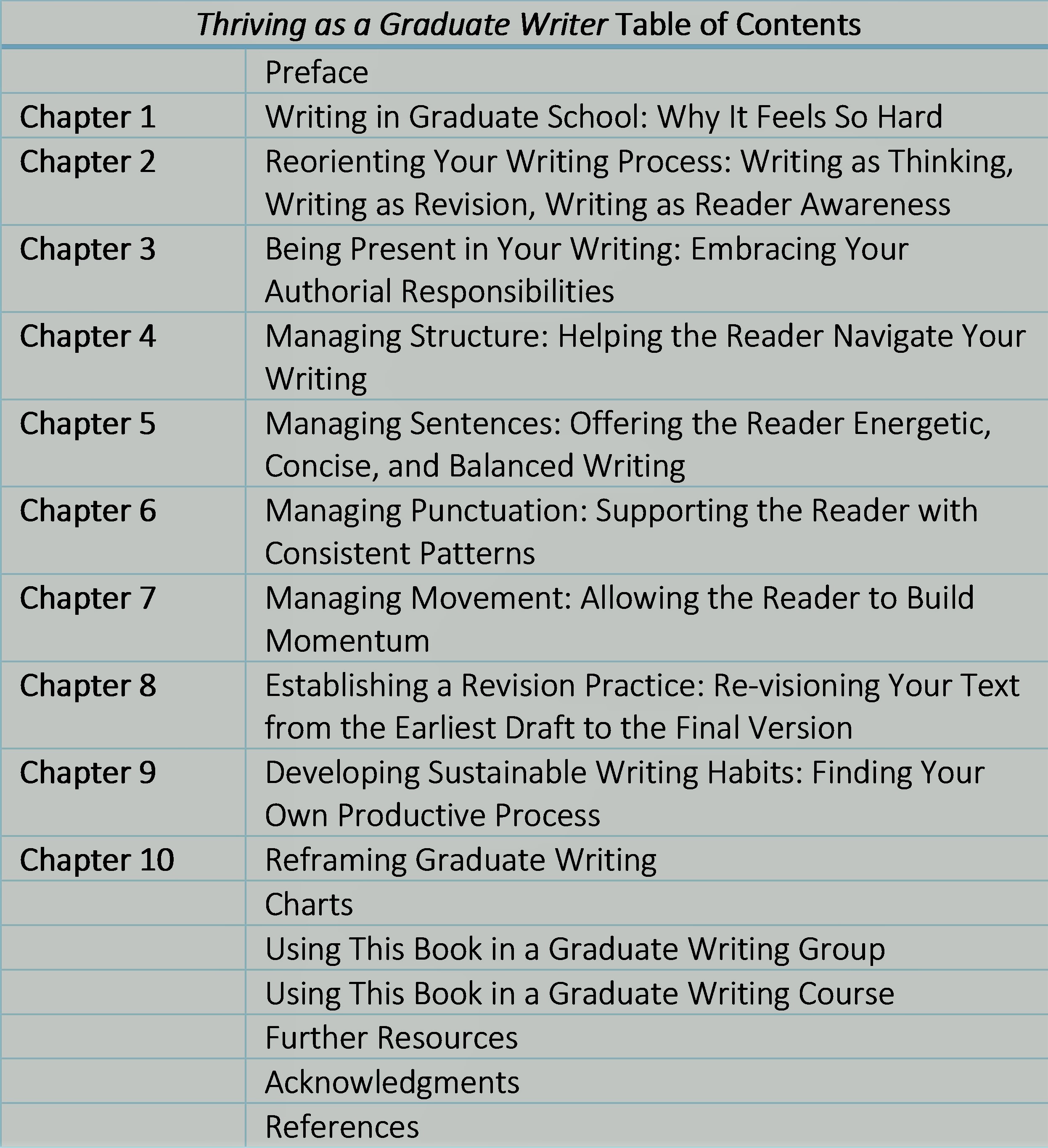

In the book, I offer a discussion of principles, strategies, and habits that I think can help. (The table of contents can be found below, so you can see the breakdown of this material.) The principles point to a way of thinking about academic writing. Since writing takes up so much time and energy, it is worth exploring foundational ideas that can ground a writing practice: writing as thinking; writing as revision; writing as reader awareness; writing as authorial responsibility. Those principles lead into concrete strategies that can transform the experience of creating and revising an academic text. The heart of this book is the five chapters that unpack these approaches to working with text: managing structure; managing sentences; managing punctuation patterns; managing momentum; and building a revision process. The final element of the book is the consideration of writing habits. Even with a solid approach to academic writing and range of useful strategies to hand, we all still need to find ways to get writing done. Graduate writers, in particular, need exposure to writing productivity advice that is rooted in their unique experience of academic writing. This chapter provides a range of strategies to help build a consistent and sustainable writing routine: prioritizing writing; setting goals; finding community; developing writing awareness; and grounding productivity in writing expertise.

This book is a short (only 226 pages!) self-study text. You can read through the whole book—in whatever way works for you—and then use it as a reference. The manner in which you refer back to the book will depend on what you currently need to concentrate on. Most readers will benefit from returning to two chapters: Establishing a Revision Process (Chapter Eight) and Developing Sustainable Writing Habits (Chapter Nine). Those chapters are organized around charts that are distributed throughout the chapter (and that appear again at the back of the book). Since every writer has their own challenges and their own optimal writing process, I urge readers to take those charts and rework them—on an ongoing basis—to suit their needs. In addition to the charts, you will also find other resources at the end of the book: guides to using the book in a graduate writing course or graduate writing group and brief account of the blogs and books that I most recommend to graduate writers.

Overall, this book aims to inspire graduate writers to think differently about the nature of writing and then offers concrete strategies for managing both their writing and their writing routines. It was a labour of love to craft the writing advice that I offer everyday—here and in the classroom—into a more coherent and enduring form. I hope it gives you the capacity to approach this indispensable part of academic life with more confidence and more enjoyment. I look forward to hearing what you think!

Thriving as a Graduate Writer is now available from the University of Michigan Press. To order your copy, visit the book page. Order online and save 30% with discount code UMS23!